Skepticism Remains About Hydrogen And Carbon Capture Systems Benefiting Our Climate Goals

Over the last 12-18 months in climate and energy circles, there’s been an enormous amount of attention and hype surrounding the potential use of hydrogen (H2) and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. The Council has written explainer blogs on each (hydrogen and CCS). Congress made significant tax credits available over the next decade for hydrogen production and for installation of CCS technology in the Inflation Reduction Act; and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) with $8 billion over the next five years to invest in 6-10 “regional clean hydrogen hubs” (or H2Hubs) across the country. The fossil fuel industry, in particular, has hyped hydrogen as a potential silver bullet, a supposedly low-carbon replacement for all sorts of fossil fuel uses that is itself derived from fossil fuels.

A simple framework for understanding how to address the climate crisis and achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century is “decarbonize the electric sector and electrify everything.” That’s a useful bumper sticker, but there are more difficult-to-abate sectors that will not as easily be able to embrace direct electrification. These include certain industrial sector activities (e.g., steelmaking, cement and chemical manufacturing, ammonia production) and heavy transportation sources (e.g., long-haul heavy duty trucking, aviation, and maritime shipping). Hydrogen and CCS could potentially serve as technology pathways to decarbonize these sources. That’s the hope anyway.

With DOE having officially released a funding opportunity announcement for H2Hubs last month (concept papers from applicants are due in early November), we must seriously consider whether Pennsylvania stands to benefit from a potential H2Hub. Can hydrogen and CCS serve as viable options for decarbonization, or are they just another distraction, another way to lock us into continued fossil fuel use and further investments in fossil fuel infrastructure? At Clean Air Council, we remain deeply skeptical that hydrogen and CCS deployment will benefit our climate goals, and we view the rush to build out “blue” hydrogen in Pennsylvania with significant concern.

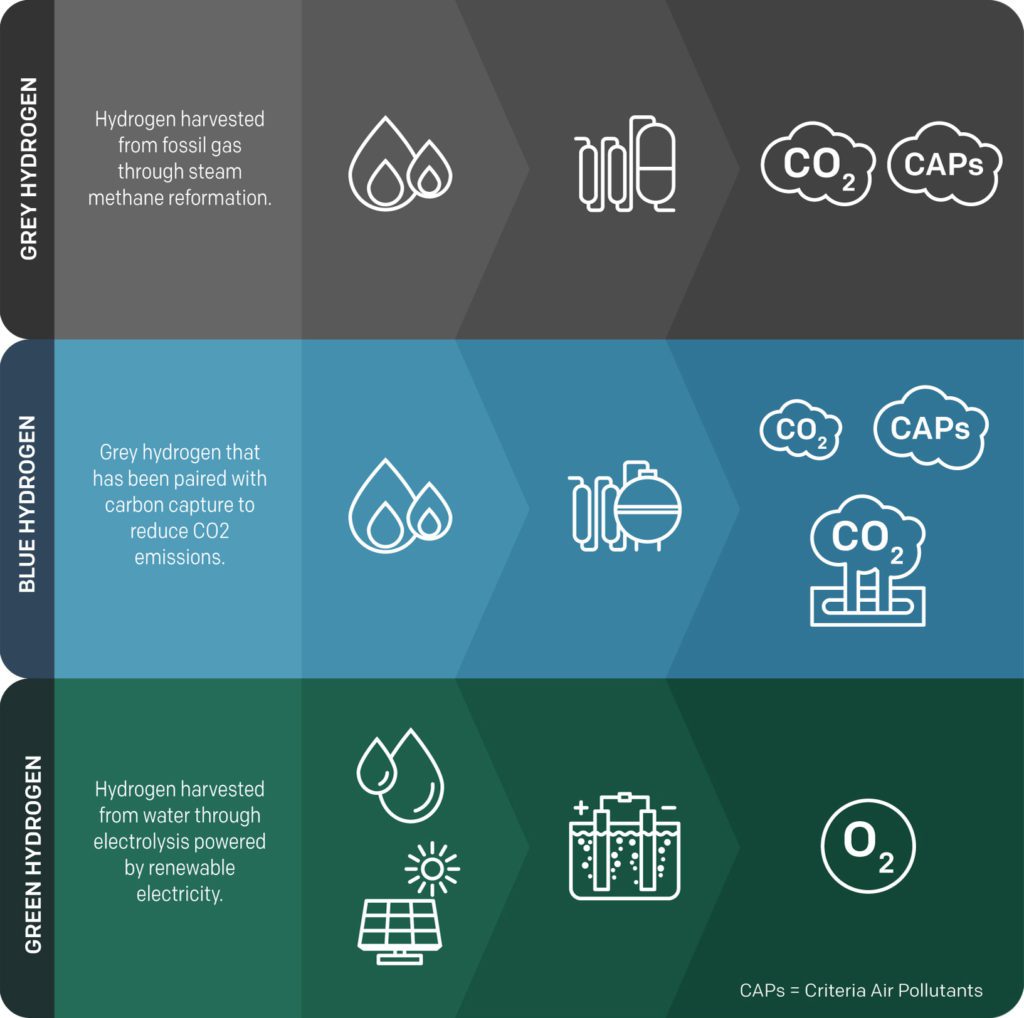

Given Pennsylvania’s massive reserves of methane gas, and given the entities most aggressively pushing for federal H2Hub funds in Southwest PA (including EQT, Shell, and US Steel), we are certain that PA-produced hydrogen would be derived from methane. That’s how most hydrogen is made today around the world, referred to as “gray” hydrogen. When paired with CCS technology at the site of production, it can then be referred to as “blue” hydrogen; that term is used very sloppily, though, because proponents don’t seem to care much about just how effective CCS technology is at actually mitigating carbon emissions. And CCS, even if it did capture 95+% of carbon dioxide emissions, would not solve the problem of greenhouse gas emissions from blue hydrogen. Methane is a very leaky gas, and Pennsylvania’s oil and gas industry already emits over 1.1 million tons of methane annually. Methane has up to 87 times the heat trapping effect of carbon dioxide, and it leaks at every stage of the gas production and transportation process. These upstream methane leaks can be mitigated by robust, comprehensive regulations at the state and federal level, but no control requirements will ever achieve zero methane leakage. And blue hydrogen production will require even more methane than gray because methane is utilized to power the CCS process. Hydrogen itself is the smallest molecule in the universe and is far more leaky than methane. While hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas, if it leaks into the atmosphere it will interact with greenhouse gases and exacerbate warming effects.

Meanwhile, CCS is a 50-year old technology with truly variable results in actually capturing and storing carbon dioxide. The majority of projects historically have used CCS for enhanced oil recovery, which is a way to produce more oil and, consequently, more emissions. Only about 10-20% of CCS projects have actually stored carbon in dedicated geological structures without using it for enhanced oil recovery. CCS is currently in use worldwide at certain gas processing plants, industrial facilities, and a very small number of electric power plants. Close to 90% of proposed CCS capacity in the power sector has failed at the implementation stage or was mothballed early. CCS, like hydrogen production, is a very energy-intensive process given the need to capture, transport, and compress carbon dioxide in order to inject it underground. The number of failed or underperforming CCS projects worldwide significantly outnumbers any successful experiences thus far.

These are all major concerns on the production side of a potential blue hydrogen hub, but we are also concerned about potential end-uses of hydrogen in Pennsylvania. There is talk in Harrisburg about using hydrogen not just in niche applications like steelmaking or for heavy-duty vehicles but also to blend it with methane at gas-fired power plants or pipe it as a heating fuel into residential homes. These are inefficient, unsafe, and wildly expensive options that must not be pursued. Hydrogen makes gas pipelines more brittle, which poses catastrophic risk of explosions. Existing gas appliances like stoves, furnaces, and water heaters are not designed for hydrogen-methane blends. And hydrogen is significantly more expensive than methane, so blending any hydrogen into city distribution systems will inherently increase ratepayer costs. Again, hydrogen is an energy-intensive resource. Its production and use incur a chain of energy conversions and losses. These losses make hydrogen a costly option for most applications, particularly where those can easily be served by more efficient solutions (renewable generation in the power sector and electric heat pumps for residential heating and cooling). Hydrogen must be deployed only when it serves the most efficient pathway to a decarbonized economy, complementing proven and readily available alternatives.

To be clear, green hydrogen is no panacea either. “Green” hydrogen is made from water via electrolysis, which is powered by renewable energy sources. Each form of hydrogen production involves different challenges and tradeoffs given its energy-intensiveness. As of 2020, Pennsylvania produces only about 4% of its electricity from renewable sources. We simply do not have excess capacity of renewable generation lying around that can be utilized for green hydrogen production. We need to massively scale up renewable energy to decarbonize our electric sector as quickly as possible. There is likely room in a decarbonized economy for green hydrogen to serve as a precious, expensive resource that has niche applications in more difficult-to-abate sectors. But that’s not what’s being talked about here in Pennsylvania.

Groups across Pennsylvania have a diversity of perspectives on whether, and to what extent, hydrogen and CCS should play a role in economy-wide decarbonization. At minimum, any production, transport and utilization of hydrogen must be: (1) subject to stringent and well-enforced community protection standards; and (2) must meet strong lifecycle emissions standards and be consistent with a pathway to net-zero GHG emissions by no later than 2050. There are so many other questions that remain unanswered. How large a footprint would an H2Hub have? How many hundreds of miles of pipelines would need to be built? How much state taxpayer money would be needed for cost-matching purposes? Clean Air Council will remain fully engaged on these issues moving forward, but we are deeply concerned that the conversations happening now – the push for blue hydrogen now – will ultimately fail to make sense from either a climate or financial perspective.